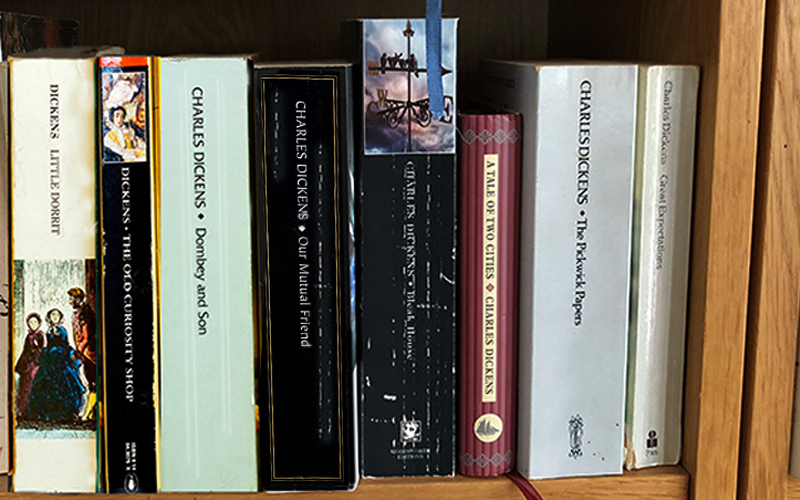

I became a Dicken’s fan early on. I remember reading David Copperfield at primary school and I gobbled up Oliver Twist. Pip and his Great Expectations hovered around my teenage years. I probably had a strange view of the world.

The thing I liked best about Dickens were the characters I met, they were nothing like the people I knew in 1970s Wellington. I would have died for friends like the Artful Dodger and his gang. They were my imaginary friends and did much more exciting things than the real ones. And because I was not long out of the fantasy & magic worlds of Narnia and Middle Earth I half believed these people existed. I knew that “Dickensian London” was a real time and place, and I read in that zone between reality and imagination. Where most history probably belongs, anyway.

One of the main advantages of Dickens now is that he’s out of copyright. Yes, you can download the entire works of Dickens onto your kindle for free. Generally, I don’t download books for free. I like to ensure the authors get paid, but that’s a rant for another time. Dickens doesn’t need my coin any more. I put him in my bag when I’m travelling and now I look forward to that four hour delayed stopover.

I suppose I’ve read Dickens on and off throughout my life. There is no end to the stories, once you’ve read the entire collection you can happily go back and start again – by that time years will have past and the stories will be fresh. They certainly won’t get any more dated.

But here’s the thing. Charles Dickens saved me.

It was when I was living in England, and my children were little, and I was an insomniac. I don’t mean the kind of insomnia when you’re a bit stressed and don’t sleep well for a few nights and whine, I’m so tired. I’m talking about the deep insomnia that can last for months, when you have no expectation of sleep at all, even though you are in that place that’s deeper than tiredness. Fathoms deeper.

It’s where you wake up at 2am and know that nothing will send you back to sleep. That’s where I was. Of course I drank cocoa, had hot baths, did yoga, said hommmmm for hours. Counted bloody sheep. Sleep wasn’t coming.

If you ever find yourself there, here’s my tip: read Dickens.

I’m not suggesting for a single second that Dickens is soporific. Quite the reverse. Reading Dickens will not send you to sleep. He’s thrilling. And anyway, you’re an insomniac. Nothing is going to put you to sleep. You may as well read. At 2am, there’s not a lot else to do.

After a while you’ll find Dickens’ characters will climb in to bed with you. They become so real, you can anticipate what they are going to do. And then they surprise you, like when a friend you know well does something out of character. The very fact that you can know a fictional character well enough to be surprised by them is a bit creepy.

When you know characters so well, you don’t even need to turn the light on or pick up the book. You can look, wide-eyed into blackness of your black room and you can play with Dickens’ characters, because you’ll know them so well. You can put yourself in the stories with them – you can take Pip in hand and tell him to forget his Great Expectations and go back to the forge, and have Pip look up at you with those big eyes and say “Yes! Yes I will go back. Joe is a good man, I’ll go home.”

Doesn’t happen in the book.

Or pick up a gun and shoot Little Nell – God knows she deserves it – and put her and generations of future readers out of their misery. I’ve done that a few times. BANG! Goodbye Little Nell. It’s very satisfying at 3am.

I’ve been thanked many times by insomniacs for that bit of advice – to read Dickens through the night. I know a teacher who received his entire classical education between 2 and 5am.

So if you find yourself falling into an insomnia that might last for months, put a stack of Dickens on your bedside table and pick some characters to romp around in bed with you. You can mix them up. I’ve got a bit of a soft spot for Inspector Bucket of Bleak House, and I sometimes take him to visit Dombey, to see if he can’t sort out that great bully. He tells Dombey to take note of little Florence: “You’re a sensible man of the world,” he says. “And a sensible man of the world knows the value of an intelligent girl.”

If you want a suggestion on where to start, try here:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…” and keep going until you have worked your way through the complete works. You won’t get any more sleep, but you will spend your nights in excellent company and get out of bed in the morning with a dramatically improved vocabulary.