Lydia Syson’s Mr Peacock’s Possessions sets the characters and the scene slowly – you need to understand the background before you can follow the story. So don’t be impatient, sit quietly as the curious and impulsive Kalala introduces you to his life in the Pacific, his brother, the pastor Solomona, and their small group of god fearing men who are shipped to an island where a white man and his family are struggling to settle.

Lizzie’s story comes next, she tells of family life on an isolated island, the difficulties faced by her mother and many children as they live castaway style, and the struggles of her delicate older brother, who is a disappointment to their very physical and driven father. Lizzie is her father’s favourite and she loves him unreservedly. Until she has to confront a truth that questions all she believes of him.

The family are swindled by a ship’s captain, they suffer rats and weevils and have some small successes, but there is an undercurrent of suspense growing. There are bones on the island, pigs’ bones, says Mr Peacock, as he hastily buries them. Kalala and the Islanders arrive, Lizzie’s brother goes missing and they all spread out over the island to search for him.

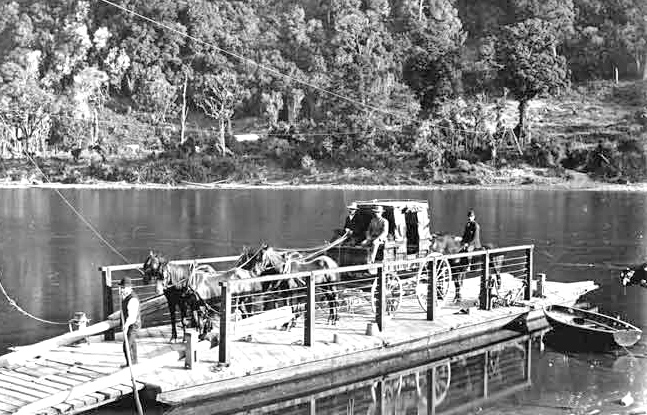

Mr Peacock is a possessive man. Lydia Syson makes his frustrations seem understandable in the rough and rugged man’s world scattered around the very edges of Victoria’s imperial petticoats. Peacock had struggled for years, as many did, slowly realising through constant failures that the dream of owning colonial land was not a promise for everyone. He owned his wife and his children and when the opportunity came to buy and island he owned that, too. Our main story begins when he brings in his “Kanaka boys,” to work his land and gradually young Lizzie and the rest of the family begin to question her father’s possessive attitudes.

Kalala and the Islanders’ story merges with Lizzie’s and a story that has gone before them on the island, and the mystery of the missing brother hangs over them all.

The reading just gets better and better and the story becomes utterly compelling. My advice is to set aside a good chunk of time when you get near the end, there are some things that need to be finished.

Mr Peacock’s Possessions is a terrific book for a book club read, there are lots of questions around possessiveness and ownership, success and failure, compassion. You can discuss colonial attitudes to women, race, land, the power of religion. I don’t think I’m giving anything away by saying Monday Island, where the Peacock’s live, is in fact Raoul Island in the Kermadecs, and now a marine reserve and a place of extraordinary biodiversity. It featured on the migration route for early Pacific voyagers and for those of us who love islands it has a fascinating history all of its own.

Head’s up for my book club – this one is my next choice.