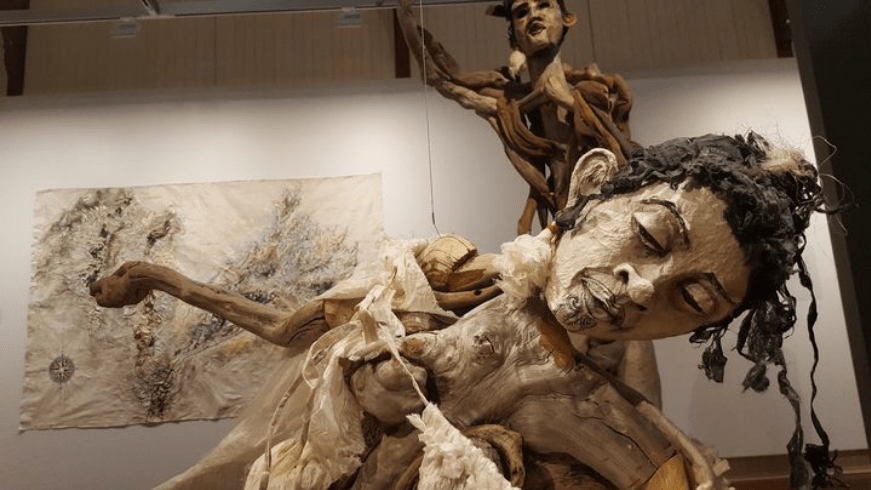

Sally Burton has created an intensely emotional work of art, inspired by the Wairau Affray. I find it extraordinary that an exhibition so poignant can come from that ugly rock in the river of our history. She has made sculptures of the armed conflict between the Nelson colonials and Te Rauparaha’s Ngāti Toa, frozen at the flashpoint when the bullet hits his daughter. If only she could have stopped time a minute earlier and said – No. Wait. We can talk, we can talk, we can talk.

The figures are crafted from driftwood bones collected from the Wairau River which is appropriate as 175 years ago the dispute began with these trees, this wood. Te Rauparaha said he could burn the surveyors’ huts because the wood, being on his land, belonged to him. Captain Arthur Wakefield said he had committed arson and must be arrested.

We call it the Wairau Affray now. Or the Wairau Incident. I do wonder why we are so reluctant to call it the Wairau Massacre. It ended in an indiscriminate and brutal slaughter of a dozen men, so no matter who the provocateurs and who fired the first shot, I think we can own up to our history and call it a massacre.

In 1843, the ownership of Wairau Valley was disputed.

Ngāti Toa had claimed it by force from South Island iwi in the 1830s, but had not settled there. The Wakefield brothers (Ernest Gibbon in England, William in Wellington and Arthur in Nelson) were convinced they had purchased it for the New Zealand Company settlers. They bought it from a woman, said to be the widow of a Captain Blenkinsopp. She had deeds for the plains of Wairau signed with elaborate drawings of the tattoos of Te Rauparaha, his nephew Te Rangihaeata and chiefs from Te Atiawa, who appeared to have sold the land to Blenkinsopp in exchange for a ship’s cannon. But had Blenkinsopp reached an agreement to buy the land, as stated in the deed, or had he just made an agreement to take wood and water from Wairau and tricked the chiefs into signing away the land, as Te Rauparaha later claimed? We can guess, but we don’t know.

It gets more complicated: the New Zealand Company also claim to have bought the land directly from Te Rauparaha in their 1839 agreement, and, for good luck, a third time from local iwi. A Sydney agent also claimed to have bought Blenkinsopp’s deeds (meaning Wakefield’s was a copy), but was prevented from taking ownership by local iwi, who disputed his claims.

There was already a land court in place in 1843, presided over by William Spain. This marked the beginnings of a complicated judicial procedure to establish who had said what to whom, and what was understood, and whether it was fair or whether the seller actually owned the land in the first place and had the right to sell. And at what point taking land by armed force became illegal. And what these disputes meant in the context of land sold on, to honest buyers. And whether, pre-Treaty, any of the European land purchases held any validity at all. William Spain had his work cut out and he was a slow, methodical man. He was working his way through disputes in Wellington, Wanganui and Taranaki. Wairau was a way down his list.

Meanwhile the Nelson settlers wanted their land. They had purchased their town and country acres before leaving England, in some cases before Nelson even existed. There was a huge pressure on the Company to open up farmland, and Wairau offered a great expanse of “waste land”, with no obvious, settled, Māori population. Captain Arthur Wakefield, the nice-but-dim NZ Company Agent in Nelson, sent the surveyors in.

Te Rauparaha brought his people across from Kapiti Island. They had protested to William Spain that the land was not given up, they threatened the New Zealand Company not to survey there. Te Rangihaeata told Wakefield if he wanted to take the land, first he would have to kill him, or make him a slave. The survey went ahead. William Spain didn’t arrive.

Te Rauparaha burned the surveyors’ huts, after first escorting the men out, unharmed, with their possessions. The huts were built from wood from his land, he said, he could burn them if he chose. And this was where Police Magistrate Henry Thompson stepped in with a matching show of testosterone and the Victorian equivalent of: Oh, no you don’t!

Thompson issued a warrant for Te Rauparaha’s arrest on a charge of arson and he armed a party of fifty-odd settlers with outdated weaponry and headed for Wairau. Arthur Wakefield went along with him, agreeing the chiefs were bullies and needed to be taught a lesson. In hindsight, it is difficult to imagine such recklessness.

The English were not an army. Most were farmers or shop keepers, rounded up for the expedition. For most Nelson settlers at this time, immigration had been a disappointment and they were a disgruntled lot, but their complaints were with the Government and increasingly the New Zealand Company rather than Māori.

In Wairau they found the well-armed Ngāti Toa camped by a stream. Te Rauparaha offered his hand to shake – the surveyors greeted him but Thompson pushed it away. The accounts from then on vary. Most agree that Te Rauparaha had offered to talk things through, the volatile Te Rangihaeata had made threats, and Thompson brought out handcuffs and foolishly attempted to arrest Te Rauparaha in front of his people. The English fixed bayonets, Captain Wakefield called them forward to assist the arrest, and a shot was fired. Neither side has admitted to that first shot.

Then the volleys went back and forth and the first dead was Te Ronga, wife of Te Rangihaeata and daughter of Te Rauparaha. The English fled, the Māori chased. There was fighting on the hillside. It was an affray.

Then Wakefield, seeing men going down, called for the English to surrender. They waved a white flag. They put their hands up and submitted to being rounded up by their captors. For the English, capture in defeat meant being taken prisoner until your allies ransomed your release. Not so for the Māori. Claiming utu for the death of Te Rongo, they executed the English by tomahawk, with hacking blows to the back of the head. Twelve of them, one after the other, while Arthur Wakefield called for peace. There are 22 Nelson settlers buried in Tuamarina in Wairau. Four Māori were killed.

That was the Wairau Massacre.

It could have tipped the whole country into war and the Pakeha would have been routed, as they had vastly inferior numbers. But somehow, the situation was temporarily diffused by talk and talk and talk, and when FitzRoy arrived as Governor a few months later, he pardoned Te Rauparaha, accepting that he was provoked and recognising the two races had cultural differences in war. FitzRoy knew he had no option. History shows the pardon was not forgiveness.

I’d like to think that, despite the systematic racism of the intervening years, we are finally coming to the understanding that viewpoints can differ but be equally valid, and we have discovered ways to deal with complex problems other than by aggression.

Sally Burton’s exhibition illustrates our painful history, but I hope comes with a message of hope for how far we have come.

__________

Sally Burton – Pale History, at Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua. 16 December 2018 – 24 March 2019. https://www.pataka.org.nz/

(Photo: RNZ / Tracy Neal)