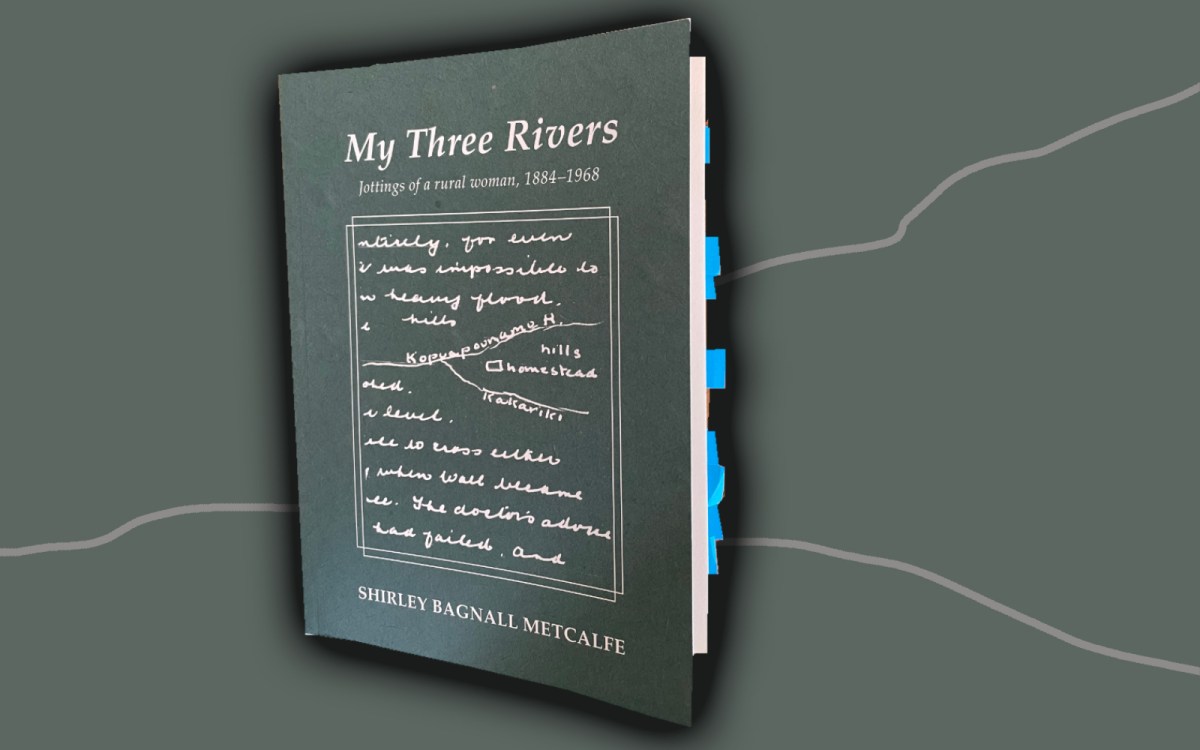

This book was a real surprise. Shirley Bagnall Metcalfe’s book on life in NZ’s early outback is subtitled “Jottings of a rural woman 1884-1968”. It sounds like it could be a bit staid. A little bit domestic. Grandmotherly, perhaps. But Shirley is a tour de force, a gutsy and practical woman with a hell of a life story and a cup that is never half-empty, despite the extremes of her life, but always, just like those bloody rivers, filled right to the brim and overflowing. She has gusto, does Shirley, and has a young, friendly voice. I wish we’d been friends. I’d have followed her anywhere.

Shirley comes from a big, happy family near the Waihou River in the Thames Valley. Boats pass and the kids learn their stories. Shirley was funny even then. “I found men very hard to understand and was inclined to agree with a woman at a meeting who applauded vigorously when she heard the remark that ‘all men need mothering’. She thought the speaker had said ‘smothering’. I just wondered! Was she right?”

She marries a bloke called Wall and they are cool together long before it was cool to be cool. The main part of the story focuses on their farm life, eking a bloody difficult living from a hillside up a valley in the serious back of beyond of the East Cape, coping with everything with that early settler make-do attitude and a good sense of humour. And love. It runs right through the book. Most of the time they are cut off from the world by the rivers, which they cross when they are low with a cart, maybe on horse back when they run higher, sometimes swimming behind the horse holding it’s tail when the river is in flood. Then the first cars arrive and it beggars belief that they took these old jalopies through the rivers and up the farm tracks. The fords and the tracks constantly wash out. They rebuild them. The rivers do their thing. It goes on.

They fix everything. Build their own house, dig their gardens. Bring in gangs of shearers and bushmen when they need them. They are mechanics and engineers and builders and farmers and gardeners and parents and educators and do all their own doctoring. There’s a first aid book (imagine it!). The chapter on some of the farm injuries is queeze-inducing, but they just patch up what they can and get on with things. “During bush felling, one of the gang was severely injured by a falling tree, his scalp was laid bare, torn around the hair line from neck to brow. With great care, Wall laid the torn flesh back, stitched it round with his flesh needle, bandaged the head, and made a really good job of it. Although it was an ugly wound it was more or less a surface one, and the man completely recovered.“

I like the ‘more or less’. The doctor was seventy miles away and if the rivers were up…well. Late 1800s I don’t imagine a doctor could do much more anyway.

They get a bunch of “neighbours” and eventually the telephone comes along, so there is a social life and, though terribly isolated, the families manage to support each other. The friendships across the farms are genuine and generous. I love the story of their teenage daughter going to a party, packing her party-dress in a waterproof bag and taking the horse through the rivers, getting picked up for short stretch by a neighbour and then crossing another river and then getting another lift and then all the same in reverse afterwards, getting home at four in the morning. She just gets on with feeding the chickens. No point in going to bed for an hour. That’s commitment. You sure as hell are going to enjoy that party.

Shirley and Wall face hard times. The war takes its toll on many families in the region. There is the slump, with a disastrous fall in prices for five years and twenty years to catch up. Sheep selling for half a crown each. There were always rising costs, difficulties in obtaining basics like fencing wire, staples, iron. Shirley explains “…we had to go carefully, until at last after many years of uphill work, we had caught up, and could begin again from scratch – but we still had our own home.” What a woman.

When they decide to sell, she is most concerned for Wall. “He had never deviated from his purpose of creating a well-run farm and a comfortable home, and of forwarding the interests of the district a whole.” She admits there had been drawbacks, but they had been happy. Their love comes through in every chapter.

They move to the Waikato in retirement, and there is our third river.

The timeline in the book is not chronological, though there are three sections grouped by the three main rivers in Shirley’s life. Within that, they come in chapters: Coast Life, Pig Hunting, Difficult Journeys, etc. Each is a well told short story. Every one is charming and full of fun and vigour. Most have a river in them which steals the show. Usually the river is misbehaving.

They really did have it good and hard in the old days. I’m left feeling a bit embarrassed by my soft self-indulgent wilting flower modern life and think a stint on a back country farm with Shirley and Wall would do wonders for us all. “In the back-country, life is not easy, but we would not understand the having without the striving.“

Shirley died in 1968 and the book has been compiled by her grandson, Andrew Wright, who deserves a medal for bringing his grandmother’s “jottings” to a new generation with such care and so beautifully. I loved reading them.

Gosh I do like the sound of this one!

LikeLike

Great review thanks! My sister has given it to Dad (Andrew) and he is quite chuffed. We will organise a medal!

LikeLike

Great review thanks! We have passed it onto dad (Andrew Wright) and agree he deserves a medal!

LikeLike