“Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth about how the world lives!” says a character in the The Covenant of Water. That’s an oldie but a goodie and is perhaps is an apt quote for this book. I’ve never been to India. But with Verghese’s story it felt as though I visited every evening, in that witching hour before sleep, when a book takes me somewhere else. Reading Verghese, as I experienced before with his first novel, Cutting for Stone, is an immersive experience.

This is a commitment book and needs to be read with some consistency. If you dip in and out and don’t pay attention you’ll lose the thread. But hey, wait until you have an appropriate window for an epic read and consume the story patiently. It’s over 700 pages long, but it’s worth it. The novel describes the experiences and thoughts of several main characters through three generations in the southern Indian region of Kerala, starting with a twelve year old girl in 1900 who is sent down the river in marriage to a man more than three times her age. Her granddaughter is the final voice in the story, who, decades of turmoil later when she is a doctor, unravels (as in many epic stories) a devastating family mystery and uncovers a personal tragedy.

The backbone of the story centres on the young bride, who evolves into Big Ammachi (grandmother), a wise matriarch of the estate of Parambil. She introduces us to the curse of the ‘Condition’ in her husband’s family, in which many of the men have a strong aversion to water, and every generation brings deaths by drowning. Initially this sounds like we’re taking a dip into magic realism, or perhaps the Condition is some kind of psychosomatic self-fulfilling prophesy with which to saddle an infant. But our author, Abraham Verghese, is a physician, vice chair of education at the Stanford University School of Medicine and a writer who loves a bit of medical mystery. There’ll be no magic here, but he will medic the hell out of it. And so in the latter sections of the book, our young doctor takes the Condition from uneducated rural India to the hospitals and medical colleges of Madras (where Verghese himself trained), and I, for one, got an eye-opening lessonon how peasant lore and sharp observation can shape medical advancement. Like many ailments described throughout history, once their cause is identified and named there comes, if not immediate relief, at least hope.

There’s a whole fascinating generation between these two women with Big Ammachi’s son Philipose; his exquisitely drawn wife, Elsie; pulayar (family servant) Shamuel and son Joppan; Baby Mol, who remains a baby throughout her life, and other characters. Village life, family interactions and local politics set the scene for more compound tragedies.

Running in parallel to this complicated story is another strand, that starts with a young Scottish doctor called Digby Kilgore, initially a misfit in the British Raj, who has a series of unfortunate events which link him, eventually, to a leprosy sanctuary and ties to Big Ammachi’s family.

All these lives come together, not only by blood, but by water.

Our young doctor, the woman who embodies hope for the future, stands with the hem of her sari in ‘the water that connects them all in time and space and always has. The water she first stepped into minutes ago is long gone and yet it is here, past and present and future inexorably coupled, like time made incarnate. This is the covenant of water: that they’re all linked inescapably.’

If that sounds a bit Gone With the Wind style grand epic, the breadth of the story sometimes does have that feel to it. These are big themes played out in the detail of individual lives. However, unlike in GWTW, here the big picture is not drawn in a sweeping civic panorama but seems so much in the background as to be almost invisible. ‘Midnight’s Children’ and the partition of India are mentioned, but not felt. There is a character who becomes a revolutionary, but his story takes place off the page and fizzles out. The rule of the Raj is mostly portrayed as benign. This is not a political book; it is more saga than epic. The crises and tragedies are personal, the universal truths that emerge are human and the details portrayed are intimate: an old cooking pot, tethered canoes by a jetty, the monsoon. ‘The sky is low and as heavy as wet sheets on a sagging clothesline‘. There are lovely descriptions of life’s rhythms in the village.

This, for me, made the experience of reading The Covenant of Water very satisfying. Even in the most turbulent of times, daily life goes on here. There is a new spice for the yoghurt, a visit from the elephant, ill neighbours, art, weather. A promise to cut down a tree that blocks the light.

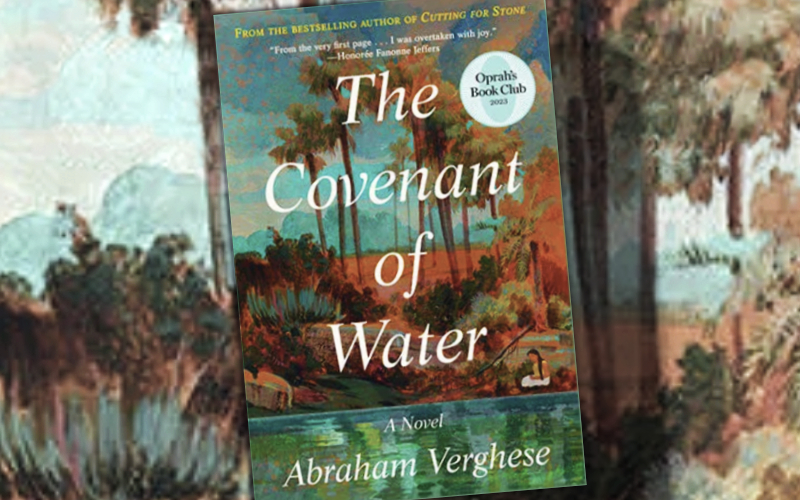

Oprah Winfrey says of The Covenant of Water, “It’s one of the best books I’ve read in my entire life.” High praise indeed.

‘It is indifferent, this water that links all canals, water that is in the river ahead, and in the backwaters, and the seas and oceans—one body of water.‘ Starter question: what is the author saying here and how might it apply to your world?

I am a Syrian Christian from central Kerala where the action in the novel takes place. Since I can personally relate to what the author writes about I felt highly elated and I can certainly say I have never experienced such emotional relations with a novel so far . At some level I felt it is relatable with Kite Runner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment. I love the connection with Kite Runner, too. As an outsider, I am so grateful that authors such as these share some of their experiences and culture with us.

LikeLiked by 1 person